From Ceramic Review, January February 1990, Number 121

Pierre Bayle’s thrown and smoke crackled terracotta pots have been shown and greatly admired in London and Cambridge. Elke Blodgett, a Canadian raku potter, visited Pierre Bayle in his pottery near Béziers, and writes about the man and his work. Pierre Bayle’s statement was recorded by C. Humboldt and translated by Elke Blodgett.

IT WAS BY CHANCE that I saw my first Pierre Bayle pots, in the Gallery Bolwig in Hannover, one of the few ceramic galleries in West Germany. Like magic the pots attracted my eyes, my hands. They wanted to be held, sensed, caressed. I had never seen anything like these pure, simple, generous classical vessel-shapes with a surface unlike any other – obviously smoke-fired terra sigillata, satinsmooth, but with a dark-stained crackle pattern that is usually found on glazed pottery. I had to meet the potter, though I was told it would not be easy. He lives in the far south-western corner of France with no easy way to reach him by bust or train. I wrote to ask if I could come, and he arranged for me to be picked up at the nearest railroad station, in Narbonne.

It is difficult not to be carried away into romantic clichés when describing the place he has chosen to work in, as remote a spot as can be found anywhere in Europe: an ancient stone farmhouse surrounded by vineyards, olive and almond trees, shaded by huge pines which in the summertime provide shelter for overnight guests. This is a poor region. Seasonal work in the vineyards provides barely enough to live on. Not even tourists would accidentally find themselves here. So there are no customers for pots like Bayle’s or any others. Nothing has changed in the century since this place served as hospital for a nearby monastery. Only the French Mirage army jets overhead on their way to the Spanish border are a vivid reminder of the 20th century.

I arrived on a wintry Sunday afternoon. and the house was filled with visitors. I did not quite know where I fitted in when I joined them around the open fire pit to share their vin du pays and loaf of bread. It took a while to get used to the accent du midi again.

During the next few days, we talked about Bayle’s way of life and his approach to his work. He is obsessed by the search for beauty and the perfect, timeless form that transcends reality. When he finds it, often after weeks of sketching and drawing, it is in the beginning nothing but an earthenware pot, until the firing gives it its life and glow. For him, form has to exist independently from its creator, and his personality must be eclipsed by it. Technique must be controlled to the point where it can be forgotten.

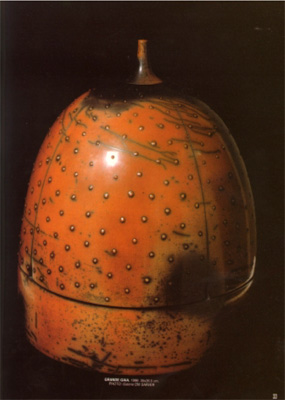

Bayle’s workshop resembles a monk’s cell rather than a potter’s studio. He sits, perfectly at ease, on the right side of an old-fashioned kickwheel, as if born to that wheel. In a corner, built into the ground and walls, somewhat like a bread-oven, is a small kiln. To stack it you have to step down into a hole and crawl into it. There are a few shelves for pots, settling jars for terra sigillata. There is little modern technology except the radio and a bare light-bulb. He needs no more. the view from the window looks on to a landscape as timeless and as ancient as his pots. Bayle’s choice of terra sigillata as a technique above any other seems obvious when related to his choice of a living space; this Mediterranean countryside bears witness to many centuries of Greek and Roman habitation and culture, to the battles of the Cathars, to scorched and burned earth. Porcelain, stoneware and glazed clays are alien here. Bayle likes to use earth, and, if need be, dig it out of a hole in his yard. Usually, though, he prefers a light clay body. After theleatherhard pots have been smoothed with a piece of sheepskin, he applies a very thin layers of red brick terra sigillata (density of about 1070 – almost water). A high soda content will flux the engobe so it resembles a lowtemperature glaze (1000ºC) even though it is less than 1/10 mm thick. On a broken pot one cannot distinguish the clay body from the applied surface, they become one.

His kiln is a small. simple brick and mud structure, wood-fired. Firewood is scarce here, so he has to use just about anything that will burn: old roots, sawdust, pine needles. The kiln, tightly packed to use all available space, takes between 7 and 12 hours to fire, depending on wind, alternating between high reduction and oxidation atmosphere as the temperature rises.

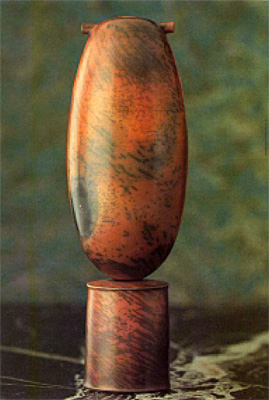

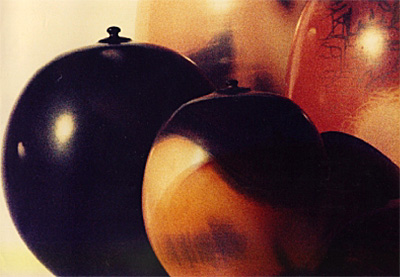

Bayle does not exactly know at what point the crazing is produced and how to control it, but if he uses a lot of sodium for deflocculation, the crackling pattern is tighter. Still, sometimes the lines seem to be following the direction of the wheel, at other times, they seem to be affected by the flame path. Much depends on luck, he says. The incredibly beautiful colours on the finished pots – flashes of jet black, grey, red, pink, yellow, ochre, gold and anything in between – are the combined results of the firing atmosphere, the way the pots were stacked in the kiln and the natural iron content (between 5 and 10%) of the engobe. Bayle never adds anything except soda to the clay used for the terra sigillata.

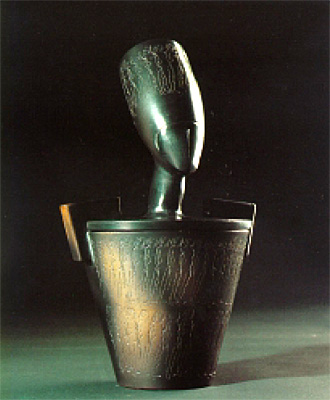

Each form, as it evolves, is named. There are the quasars, the skyphos, the flutes, the alabaster, palladio, etc. and even a Hans Coper – all admitted cultural references. Outside his studio, retaining walls built from rejected pots provide a history of the evolution of these forms and of his search and are visible proof of the high standards he sets himself. Recognition by collectors and fellow potters, honours and prizes, do not seem to affect Bayle: so what if he is “Chevalier des Arts et Lettres,” or the youngest French artist ever to be awarded “Le Grand Prix National des Métiers d’Art.”

“In spite of his closeness to nature and to the world he lives in, there is nothing mystical about Bayle’s approach to his art. Above all he is an aesthete and perfectionist, even if, at times, this interferes with inspiration. As he phrases it: “Il faut que ça soit beau. Le reste, je me’en fous. Ce n’est que le la théorie ça.”

Pierre Bayle Talking

“My approach to my work is indeed completely ambiguous,” he says. “Craftsman? Potter? I have more of a sculptor’s attitude, but I don’t want to be a sculptor … I could be, but not in the sense one understands it today, rather in the sense of the end of the 19th century, or of the early 20th. I am interested in those who create tension in space. Do I achieve that? I believe, in any case, that I manage to create tension on my pots.

A true potter, touches, loves clay. Claude Champy, for example. But with my pots, bowls, my round shapes with a tiny lid on top, one does not know if they are made from clay, metal or wood: the functional aspect is somewhat lost. I love clay, but not that much! I touch the clay, but I try to erase that gesture. Maybe because I want people to forget. I want them to see what I create as an entity which is beautiful. Clay is what I have learned about, I know how to use it, but what interests me above all is beauty. There is nothing mysterious for me about working with clay.

“If I had to talk about my approach to my work, I would have to talk about a pyramid. About balance. On the one hand there is the technical aspect, on the other, the spiritual. If one can make both sides rise together, one has a work of art. If one rises faster than the other, one has nothing.

“A potter’s technique takes years to perfect. A few days are enough to learn how to kick a wheel, but it is already more difficult to centre the clay. It has to be the right consistency. Then the position of the hands has to be considered, the fingers, the length of the arm, the precision of motions. I began with lumps which filled my two hands. Centring, opening, pulling up … After a year, you throw 10 to 50 pots a day. After 3 years, maybe 60. After ten years, 120 to 250. It all depends on the clay body, of course. With the Sèvres porcelain, a clay which is like butter, barely manageable, one manages to make 2 pieces an day when one works with a margin of 1/10 of a millimetres.

“I stared when I was 14. Now I am 45. At first, I worked in a small flowerpot factory in the province of Aude. That is where I learned the craft. Then I was production thrower in several studios in Paris and the provinces.

“When one is a labourer, there are two facts to consider. One has to produce exactly the required form. And the greatest possible number of pieces. I got so tired of production work; I did not feel like making ugly things anymore. To work for the large stores, the souvenir shops of Carcassonne or Lourdes. Even the classical forms (Empire, Louis XV, Louis XVI) are not necessarily beautiful either. But I still continue to return once a year to work in an old potter factory. For 10 days, I recover a bit my function as thrower, as labourer. I throw large garden pots, huge oil pots, 25kg of clay. I try to make them very beautiful. It feels good.

“I spend much time looking at nature. certain potters have a mystic approach to life, worry about the Cosmos. I only look at plans, insects, nature, the bodies of people. My pots have bellies, necks, breasts, shoulder …

“It is not the clay which decides the forms I make. When I settle down at my wheel, I already have a form in my head which I have drawn hours, days, weeks ago.

“For more than I year, I sketched columns and I threw some on my wheel. I was never satisfied. They were nothing but fragmented columns. I threw them all away. I was fed up. I thought about it .. A column is a sculpture and I am not a sculptor. I am a potter. The sculptor carves a column, the potter shapes a pot. So then I made a column with a small lid: that was it. One is too pretentious!

“That moment started a whole series of columns. The lid turned into a chalice. Later, another form evolved when I wanted to create an object in homage to Hans Coper, a dead potter, a character who cared about his form like I do. The column became a supporting pedestal, a foot which only served to emphasize the ear lugs. It took six years to develop the alabaster.

“One has to be patient. It is not terrible to fail with an object. On the contrary, it is something gained, nothing is lost. I shall start over again. “I know when a form is beautiful. It arrives. I seize it, but it does not come for free: there are years of work behind it. When I see it, I recognize it at once; I am categorical.

“I never sell a pot I do not love. It does happen that I give one to a neighbour if he asks me for one because he needs it. I give it away. I don’t sell it. Or else, I try to break as many as possible.

“Sometimes I rage like a whirlwind in my studio, nothing works out. I don’t necessarily look like I am working, but my head is thinking … I am always searching, every day and all day long. Right now, I am into bodies, busts, which I would like to dress, and I don’t manage.

“A potter’s work is very lonely and rather silent. I listen a lot to the radio … France-Culture.”

Photographs – Individual pots & close ups by Jean-Pierre Lefevre – others by Elke Blodgett.